By John T. Misskelley

THE ESTABLISHED SETTLER

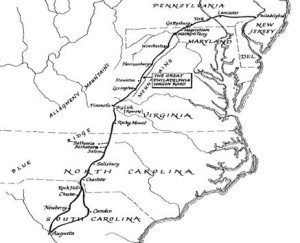

There were two types of settlers who traveled the great Philadelphia Wagon road. The first were the established families, who had been able to pay the passage from the north of Ireland to Philadelphia . The Londonderry Journal noted in 1773 that, “The great part of these emigrants paid their passage, which at 3 pounds 10 shillings each.” And, “Most of them people employed in the linen manufacture, or farmers.” [1] These people had been in the country for several years. They owned land and had improved it. But the need to enlarge their Plantations was cost prohibitive. The steady influx of Scots-Irish immigrants into the tri-county area of York , Chester and Lancaster , Pennsylvania made land very expensive. They were unwilling or could not afford to pay the prices for additional land. But they had another alternative. Land in the western portions of Virginia , North and South Carolina were becoming available. One such settler, James Muskelly applied for two separate land grants in North Carolina . Grant #146 for 100 acres was issued on April 25, 1767, and was described as: “On the waters of Turkey Creek, joining the land he bought of John Moore on the south side and running towards McNabb’s.” [2] His second acquisition was Grant #147 for 100 acres and was also issued on April 25, 1767. Both grants were entered on September 22, 1766. The description of this piece of property was entered as: “On the waters of Turkey Creek, joining the South-East corner of land patented in the name of John Moore .” [3] Both grants were issued by his excellency, William Tryon, esq. Captain-General, Governor and Commander-in-Chief, and both were surveyed by William Dickson. Chain bearers were John and Thomas Garvin. As shown above, James Muskelly had already bought John Moore’s property of almost 200 acres. Thus, we must assume that James Muskelly was established in Pennsylvania , before immigrating to North Carolina . James, seeing that to purchase additional land, adjacent to his own Plantation was impossible, he possibly made the journey to Mecklenburg County by himself to see the land and to see what was available. If that was the case, he found that the land next to John Moore’s property was, as yet un-claimed. By purchasing the Moore property and filing claims for land grants of the adjoining lands, he was able to amass almost 400 acres of virgin land. Another possible reason for leaving was family. A clachan was typically a community of related families, which made the whole more self-sufficient, and also provided more security for the pioneer families. As previously noted, the chain bearers for William Dickson, the surveyor, were John and Thomas Garvin. The Garvin family also owned land on Turkey Creek and later, James Muskelly (Miskelly) bought additional property from John Garvin. James’ daughter, Jean later marries Thomas Garvin. [4] Another family nearby, were the Clarks . James’ wife Jean was a Clark , and later Alexander Clark taught James’ son William the art of gunsmithing. [5] Once James committed to purchase the Moore tract, and filed his claims for land, he left the area and returned home. Selling his property in Pennsylvania was probably very lucrative, and he could have possibly doubled or tripled his initial investment. As the family prepared to leave, it was essential that only the most important items were to go. Tools would have occupied much of the wagon. To build their new home and to work the land, they would need hoes, axes, froes, saws, draw knives, chisels, augers and an adz. A bag of seed corn for their first crop would also be necessary, as well as feed corn for the oxen, horses, milk cow, and possibly sheep. Not to mention packing enough food for the journey. The spinning wheel was a necessity and it also had to go. As well as the bed frame and the feather mattress. Extra clothing, a looking glass and all the pewter and wooden tableware and utensils. An iron pot and a lesser pot, a griddle, the good chairs and the walnut table and chest. Now the journey began. Reverend Hugh McAden a Presbyterian minister who accepted a call from the Hanover Presbytery to preach from Virginia to Georgia made these comments in 1759,”Alone in the wilderness. Sometimes a house in ten miles, and sometimes not that.” Near Augusta Courthouse he “stayed for dinner” at Mr. Poage’s, “the first I had eaten since I left Pennsylvania .” [6] Also in Augusta County in 1752, Bishop August Spangenberg remembers, “there the bad road began. It was up hill and down, and we had constantly to push the wagon, or hold it back by ropes that we fastened to the rear.” [7] This journey could take as long as six weeks. Finally in North Carolina they soon entered the 98,985 acres of the Moravian settlements. On November 24, 1752, Bishop Spangenberg spoke of the wildlife that surrounded them, “The wolves here give us music every morning, from six corners at once, such music as I have never heard…” and, “The land is very rich, and has been much frequented by Buffalo, whose tracks are everywhere…” [8] From Salem, the land was rolling hills, open prairie and more virgin forest. On some days when the weather was good and the land firm and packed, they could make twenty miles. On other days, when it rained, it was possible to sink the wheels up to the axels in the sucking red Carolina mud, and not make three miles. And finally after much determination, the Catawba River was reached. Their last major obstacle, this river is full of huge boulders and sharp angled rocks. It looks almost, as if God had taken a handful of these boulders and tossed them to where they now lie. Added to the boulders was the green slippery moss that seemed to grow on every stone. With the oxen’s steady step and with everyone in your family helping push the wagon over the sharp stones, they finally forded their last river. Soon, they occupied their new land. THE INDENTURED SERVENT The life of an indentured servent was generally anything but pleasant. The length of an indenture was from three to ten years. At the end of their service, they received, a land grant or clothing, tools or animals, and were expected to contribute to society. As early as 1634 indentured servants were in use, as noted in the indenture of Simon Trott of Plymouth, Massachusetts his indenture read, “serve Barnes till he be twenty three years of age, and the sayd John, or his heirs, or asignes to giue him a cow calfe, at least eight or ten weeks old, live like, and to perform what else is expressed in his indentures.” [9] Many different tasks were assigned to newly arrived refugees. From working at an Iron works, or to farming or carpentry or any job that your master required. The amount of time they spent working off their indenture, seemed to be the easiest part of their acclimating to their new society. Before they even reached the North American shoreline, they had made the decision to leave their ancestral home and to find passage to the America’s. Johann Georgius Gerlinger [10] was a twenty-one year old who left Germany, where he made his way down the Rhine River to the port town of Rotterdam in Holland. As he was young he was able to secure passage on one of the overcrowded ships, which regularly set sail for Philadelphia. He would fetch a good price from the merchants in Philadelphia. The trip would last about ten weeks. The trip was very difficult as sea sickness and other illness’ would ravage the occupants of the ship, and many would die before reaching America. Once they arrived, the most dangerous part of their journey was over. Now, the next part was to try and sell their services for the shortest time possible. Proof of this is in the account of the Reverend Henry M. Muehlenberg, writing in the 1760’s that “Before the ship is allowed to cast anchor at the harbor front, the passengers are all examined, according to the law in force, by a physician, as to whether any contagious disease exists among them.” And, “Then announcements are printed in the newspapers, stating how many of the new arrivals are to be sold. Those who have money are released. Whoever has well-to-do friends seeks a loan from them to pay the passage, but there are only a few who succeed. The ship becomes a market-place. The buyers make their choice among the arrivals and bargain with them for a certain number of years and days.” [11] Once the newcomer and the merchant agreed to a specified time of service, they went to the master of the ship, where the merchant paid for the passage. If they chose wrong, and were indentured to a mean and or unfair master, the time of indenture would seem to last forever. There are many accounts of run-away servants in the local papers of the time. After three, six or ten years, they were finally free. They were presented with their “gifts” and set off on their own. Now, what was expected of them. If their indenture was in the Philadelphia area, they knew that to be able to find available land was next to impossible, so they then set their sights to the South. Organizing a trip down the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road was something that may take awhile. First they had to acquire some type of pack animal to carry supplies such as tools or extra clothing or generally everything that they owned. A weapon was a necessity. The York, Chester and Lancaster areas in Pennsylvania were well stocked with German gunsmiths who had brought their trade from overseas. Once a person was properly equipped he could then set his sights southward. Ahead of him, lay hundreds of miles of wilderness, full of hostile Indians and wild animals. The newly released indentured servant had generally the same experiences as those who traveled the road before him. After months of traveling, they reached the upper piedmont area of North Carolina. In the early years of the 1770’s, there was a thirty-mile, north-south section of land, which was deeded to South Carolina. It was called the New Acquisition and ran from the Catawba River, Just south of Charlotte Town, all the way west into the lower Cherokee towns. The low country gentry of South Carolina who lived in their beautiful homes in Charles town and the rice planters all along the coast of this province, saw the need for a buffer between them and the Cherokees and other warring Indians, who might disrupt their peaceful lives. They thought that if more Indian land was opened to settlers, then it became much safer for them to live in the lap of luxury. The Government of South Carolina began issuing land grants to all who wanted them. This is what the newly released indentured servant saw when he reached South Carolina, and occupied his new land with towering hardwoods and delicious clean water. It would seem like a dream that only after eight or ten years of being in the country, that he would now be a land owner. That is of course, that he survived the Indian attacks in which the Indians were outraged that Whites would settle on their ancient hunting grounds. He and later his family would live in fear until the Indians were pushed all the way to their upper settlements and beyond. Then the War for Independence began.

[1] From Ulster to Carolina, by Tyler Blethen and Curtis Wood, Jr. Published by Western Carolina University. The Mountain Heritage Center. Pg.14

[2] Dept. of Cultural Resources Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, N.C. Sec. Of State land grant records, warrants, surveys and related documents. Mecklenburg Co. file #1622

[3] Dept. of Cultural Resources Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, N.C. file #1623

[4] Thomas Garvin was a veteran of the Revolutionary War, and fought alongside his brothers-in-laws William And James Miskelly. Thomas and Jean moved to Pendleton District after the war, where Jean died. Thomas Garvin eventually settled in Virgo County, Indiana, where he dies. They leave a large family.

[5] Records show that Alexander Clark, gunsmith lived in York District, S.C and in Pendleton District. It seems that William Miskelly learned the gunsmith trade from Alexander. William Miskelly named his son Alexander (not proven, but highly suspected) who also became a gunsmith.

[6] Quote from The Great Wagon Road by, Parker Rouse, Jr. Published by the Dietz Press 109 E. Cary St. Richmond Va. Pg. 59-60

[7] ibid pg. 73

[8] ibid pg. 73

[9] Simon Trott, his appearances in the Plymouth Colony Records. http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/users/deetz/plymouth/trottrec.htm

[10] For genealogical information concerning Johann Georgius Gerlinger, see the Garlinger family home page at: www.garlinger.com/garfam/d0/i000521.htm

[11] Quote from the Garlinger family homepage at: www.garlinger.com/garfam/d0/i0000521.htm